The Ego, the Self, love, and science. I

Who am I? Have you ever thought this question to yourself as you lie awake in bed at night? I want to explain what it means to me, how I see that it affects me as a solitary human being, and how this affects us in the grand scheme of things. I will use philosophy, spiritualism and religion, as well as science to express my thoughts and ideas of this topic that has been heavily weighing in on my mind for the past year or so.

Philosophy

Using Jungian psychology as a modality to explain concepts of the Self and Ego. Carl Jung defined the Self as a unification of the unconsciousness and consciousness. From birth, Jungian theory dictates that every individual has a whole sense of Self, but as a person develops there evolves a separate ego-consciousness in the first half of life. In the second half of life, once the distinction within ourselves has occurred, a person becomes anchored to the external world and rediscovery or self actualization occurs and a return to true individualism.

Spiritualism/ Religion

In Buddhism, it is taught that the Ego alone is a false perception of the Self. Ego in one's self is the root of attachment. As long as we are driven by attachment, which follows the wrong conceptions of our ego, everything we do will always be superficial. Buddha taught that all phenomena, including thoughts, emotions, and experiences, are marked by three characteristics, or “three marks of existence”: impermanence (anicca), suffering or dissatisfaction (dukkha), and not-self (anatta). These three marks apply to all conditioned things—that is, everything except for nirvana. According to the Buddha, fully understanding and appreciating the three marks of existence is essential to realizing enlightenment. Nothing in this world is static, which is blatant. However, we often relate to things as if though their existence were permanent. So when we lose things we think we can’t live without or receive bad news we think will ruin our lives, we experience a great deal of stress. Nothing is permanent, including our lives. Dukkha, suffering/dissatisfaction, is among the most misunderstood ideas in Buddhism. Life is dukkha, the Buddha said, but he didn’t mean that it is all unhappiness and disappointment. Rather, he meant that ultimately it cannot satisfy. Even when things do satisfy―a pleasant time with friends, a wonderful meal, a new car―the satisfaction doesn’t last because all things are impermanent. Anatta—not-self, non-essentiality, or egolessness—is even more difficult to grasp. The Buddha taught that there is no unchanging, permanently existing self that inhabits our bodies. In other words, we do not have a fixed, absolute identity. The experience of “I” continuing through life as a separate, singular being is an illusion, he said. What we call the “self” is a construct of physical, mental, and sensory processes that are interdependent and constantly in flux.

In religions all over the world there is the story of Adam and Eve. I believe this is an across the board allegory for the abandonment of the true Self by indulging in the Ego. Because who are we but not gods or masters of our own universes, our own lives? In the Book of Genesis of the Hebrew Bible, chapters one through five, there are two creation narratives with two distinct perspectives. In the first, Adam and Eve are not named. Instead, God created humankind in God's image and instructed them to multiply and to be stewards over everything else that God had made. In the second narrative, God fashions Adam from dust and places him in the Garden of Eden. Adam is told that he can eat freely of all the trees in the garden, except for a tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Subsequently, Eve is created from one of Adam's ribs to be his companion. They are innocent and unembarrassed about their nakedness. However, a serpent convinces Eve to eat fruit from the forbidden tree, and she gives some of the fruit to Adam. These acts not only give them additional knowledge, but it gives them the ability to conjure negative and destructive concepts such as shame and evil. God later curses the serpent and the ground. God prophetically tells the woman and the man what will be the consequences of their sin of disobeying God. Then he banishes them from the Garden of Eden. Neither Adam nor Eve is mentioned elsewhere in the Hebrew scriptures apart from a single listing of Adam in a genealogy in 1 Chronicles 1:1, suggesting that although their story came to be prefixed to the Jewish story, it has little in common with it. The myth underwent extensive elaboration in later Abrahamic traditions, and it has been extensively analyzed by modern biblical scholars. Interpretations and beliefs regarding Adam and Eve and the story revolving around them vary across religions and sects; for example, the Islamic version of the story holds that Adam and Eve were equally responsible for their sins of hubris, instead of Eve being the first one to be unfaithful. The story of Adam and Eve is often depicted in art, and it has had an important influence in literature and poetry. Another vibrant tale in our written history of something so familiar. But of course, the Ego. The garden of Eden being a metaphor for a realization of the Self and a dissassociation of the falsehood of identity. The shame in their nakedness once eating the forbidden fruit speaks to a sudden physical attachment to material Earth and the given false meanings of good and evil. In reality these concepts are merely constructs of man.

Science

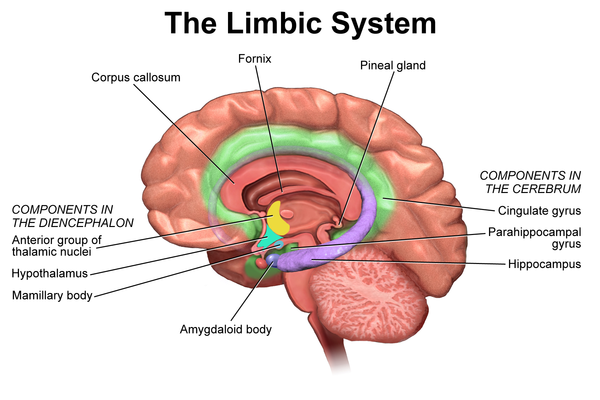

Looking to neuroscience to understand these concepts, covering the limbic system first: it is amongst the oldest parts of the brain, evolutionarily speaking, and can also be found in fish, amphibians, reptiles and other mammals. It moderates functions that have to do more with behavioral as well as emotional responses having to do with survival like the flight or fight mode, and which is why it is sometimes said that it is the control center for "lower brain functions." However, it's also responsible for memories. The limbic system employs the amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and cingulate gyrus.

The Amygdala Small almond-shaped structure; there is one located in each of the left and right temporal lobes. Known as the emotional center of the brain, the amygdala is involved in evaluating the emotional valence of situations (e.g., happy, sad, scary, pleasurable). It helps the brain recognize potential threats and helps prepare the body for fight-or-flight reactions by increasing heart and breathing rate. The amygdala is also responsible for learning on the basis of reward or punishment. Due to its close proximity to the hippocampus, the amygdala is involved in the modulation of memory consolidation, particularly emotionally-laden memories. Emotional arousal following a learning event influences the strength of the subsequent memory of that event, so that greater emotional arousal following a learning event enhances a person’s retention of that memory.The Hippocampus Found deep in the temporal lobe, and is shaped like a seahorse. It consists of two horns curving back from the amygdala. Psychologists and neuroscientists dispute the precise role of the hippocampus, but generally agree that it plays an essential role in the formation of new memories about past experiences. Connections made in the hippocampus also help us associate memories with various senses (the association between Christmas and the scent of gingerbread would be forged here). The hippocampus is also important for spatial orientation and our ability to navigate the world. The hippocampus is one site in the brain where new neurons are made from adult stem cells. This process is called neurogenesis, and is the basis of one type of brain plasticity. So it’s not surprising this is a key brain structure for learning new things.

The Thalamus and Hypothalamus Both associated with changes in emotional reactivity. The thalamus (sensory “way-station” for the rest of the brain) is primarily important due to its connections with other limbic-system structures. The hypothalamus is a small part of the brain located just below the thalamus on both sides of the third ventricle. Lesions of the hypothalamus interfere with several unconscious functions (such as respiration and metabolism) and some so-called motivated behaviors like sexuality, combativeness, and hunger. The lateral parts of the hypothalamus seem to be involved with pleasure and rage, while the medial part is linked to aversion, displeasure, and a tendency for uncontrollable and loud laughter.

The Cingulate Gyrus Located in the medial side of the brain next to the corpus callosum. Its frontal part links smells and sights with pleasant memories of previous emotions. This region also participates in our emotional reaction to pain and in the regulation of aggressive behavior.

The Basal Ganglia A group of nuclei lying deep in the subcortical white matter of the frontal lobes that organizes motor behavior. It is in charge of habit formation, movement, learning and reward processing.

Puberty is the beginning of major changes in the limbic system - one could equate this to the beginning of "second-half of life" as stated in Jungian belief or the part of Buddhism that employs the ying and yang dogma of reeling in the Ego and not letting it control the self. Part of the limbic system, the amygdala is thought to connect sensory information to emotional responses. Its development, along with hormonal changes, may give rise to newly intense experiences of rage, fear, aggression (including toward oneself), excitement and sexual attraction. Over the course of adolescence, the limbic system gradually comes under greater control of the prefrontal cortex or PFC (an area associated with planning, impulse control and higher order thought). As additional areas of the brain start to help process emotion, older teens gain some equilibrium and have an easier time interpreting others. But until then, they often misread others like any authoritative figure. We've all had our angst phase. However, this increased cognitive control over emotional responses is not limited to an individuals growth over the expanse of their existence congruent with the process of self actualization.

The first granular PFC areas evolved either in early primates or in the last common ancestor of primates and tree shrews. Additional granular PFC areas emerged in the primate stem lineage, as represented by modern strepsirrhines. Other granular PFC areas evolved in simians, the group that includes apes, humans, and monkeys. In general, PFC accreted new areas along a roughly posterior to anterior trajectory during primate evolution. A major expansion of the granular PFC occurred in humans in concert with other association areas, with modifications of corticocortical connectivity and gene expression, although current evidence does not support the addition of a large number of new, human-specific PFC areas. As aforementioned, the maturation of the PFC and its increasing control over emotional responses could be metaphorically linked to the sudden paradoxical self awareness bequeathed to Adam and Eve.

To be Continued...

Update: 06/22/24

16 pages deep in a word doc. Will post in the future. Lol.

[ x ]

Are there going to be more posts?

ReplyDelete